Share This:

The term orthographic mapping slipped around my head for a year before I felt I could finally grab it and understand. If I struggled to master the concept, I thought others may too. So today, I want to break down orthographic mapping in a way that won’t leave you banging your head against the keyboard. Hopefully.

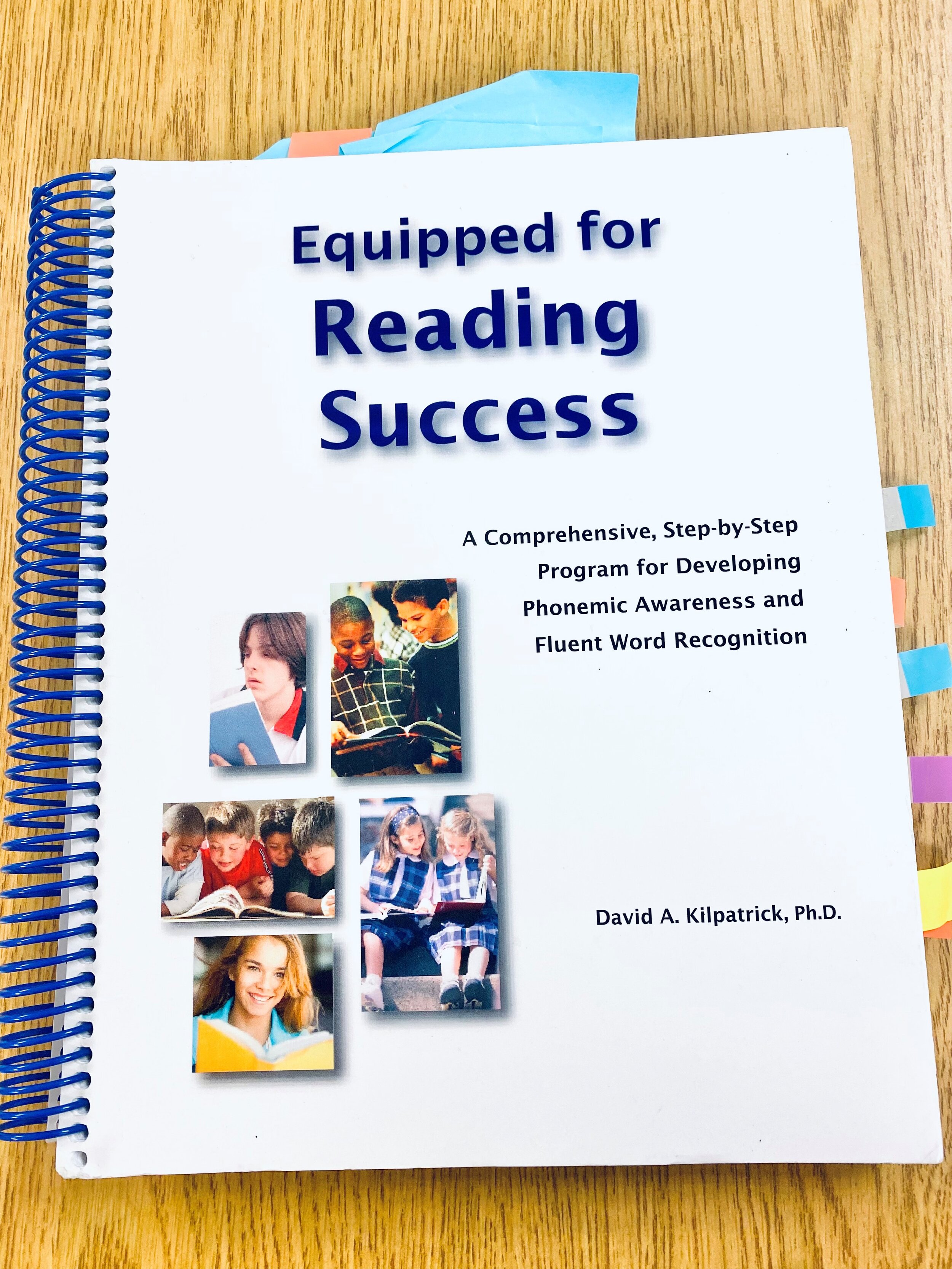

According to David Kilpatrick, orthographic mapping is “the mental process we use to permanently store words for immediate, effortless retrieval”(Kilpatrick, 2016 , p.31). Essentially, orthographic mapping is how we turn unfamiliar words into sight words. Immediate and effortless are key characteristics. It is also important to remember that this is a mental operation, not an activity. We can practice activities that promote this process, but this work is done in the mind.

Orthographic mapping is such a difficult concept to understand because of two reasons: it is an unseen mental operation, and it goes against how we intuitively feel reading happens. Most of us feel that reading is a visual task. We look at words and then we identify them by sight, right? The truth is, however, that the only visual component of reading is the letters themselves. We do not take mental pictures of words and bring up those pictures later when needed.

Think about this—are you able to read words that are in another font? What about words that have been written in all caps? Of course we can. If we can easily read words in multiple fonts, multiple handwritings, and in all caps, it simply can’t be a visual activity. There is no way we have mentally stored a visual representation of every single word in every single font. It just isn’t possible.

So how do we store words in our brains so that they are effortlessly and immediately known? Turns out, reading has a lot to do with our phonemic awareness. David Kilpatrick (2020) compared the English alphabet to that of the Chinese character-based writing. In Chinese, a single symbol can represent a word. In English, however, we do not use individual symbols (i.e. letters) to represent words, instead we use letters to represent sounds. Our writing system is based off the notion that we use letters to represent sounds. Those representations of sounds (letters) then make up words. So while it may seem that we use just our visual input to store words, having phonemic awareness is key.

In order to orthographically map, we need 2 things: phonemic awareness and letter sound knowledge. When we orthographically map, we take the known phonemes of an oral word, and then map those phonemes onto the graphemes that they represent. Because the word is both familiar and meaningful to us, we remember it. It takes only 1-5 exposures for good readers to orthographically map words (Kilpatrick, 2016, p.30). When we have familiar, meaningful letter strings, we are able to store those in our brain and later retrieve them seemingly effortlessly.

So simply put, orthographic mapping is when the oral language we know combines with the written form to create sight words. The letter strings are both familiar and meaningful, and so we store them away until we need to read them, seemingly effortlessly. When we see a string of letters that have meaning to us, our brains automatically pull that word and its meaning out.

What about decoding? It is important to note that decoding is not the same as orthographic mapping. When we decode, we are using sound-symbol relationships. The difference is, however, that decoding helps us to identify unknown words that are then (hopefully) orthographically mapped. Decoding helps us to orthographically map words, but it is not instant. Decoding words takes time and conscious effort—words that are orthographically mapped do not.

Our instruction must focus on sound-symbol relationships. We have to ensure that students are phonemically aware and have automatic letter-sound knowledge. That is the absolute minimum. There is no skipping over those steps. In my next blog post, I will explore several specific strategies that can promote orthographic mapping. I’m also hosting a Facebook live on September 15 about this topic. (Recording will be available afterwards.)

The best advice I’ve received about orthographic mapping is this: don’t expect to get it right away. I’ve read and reread Kilpatrick in an attempt to write this post. I’ve watched You Tube videos and printed articles. It is not an easy concept, so don’t feel you have to be an expert on it right away. For now, take time to digest the information. Come back in two weeks to discover classroom activities that can promote orthographic mapping. Ask me questions in the comments below!

David Kilpatrick’s presentation, “How We Remember Words, and Why Some Children Don’t.”

Equipped for Reading Success (Book)

Reading League presentation on Orthographic Mapping.

Kilpatrick, D. (2016) Equipped for reading success.* Casey & Kirsch Publishers.

The Reading League. (January 26, 2017). Orthographic mapping: What it is and why it’s so important.

. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XfRHcUeGohc&t=5s

Walsh University Literacy Initiative. (July 25, 2020). How we remember words, and why some children don’t.

. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=54J5llogLuc

*As an Amazon affiliate, I may receive a small commission on items purchased through my link. This is at no cost to you, and helps me to continue to provide weekly free content!

Share This:

Savannah Campbell is a K-5 reading specialist. She has taught her entire 12-year teaching career at the school she went to as a child. She holds two master’s degrees in education from the College of William and Mary. Savannah is both Orton-Gillingham and LETRS trained. Her greatest hope in life is to allow all children to live the life they want by helping them to become literate individuals.

Savannah Campbell is a K-5 reading specialist. She has taught her entire 12-year teaching career at the school she went to as a child. She holds two master’s degrees in education from the College of William and Mary. Savannah is both Orton-Gillingham and LETRS trained. Her greatest hope in life is to allow all children to live the life they want by helping them to become literate individuals.

Feeling overwhelmed with all the terminology out there? Want to know the key terms all teachers need to teach phonics? In this FREE Rules of English cheat sheet, you get a 5 page pdf that takes you through the most important terms for understanding English—you’ll learn about digraphs, blends, syllable types, syllable divisions, and move. Grab today and take the stress out of your phonics prep!